It’s always important to know your history – to know where you’re going, you must know from where you came.

At Trigo today, we are growing beyond frictionless checkout – constantly unlocking additional products and capabilities for grocery retailers to improve the shopping experience, boost operational efficiency, and achieve a better ROI. As we continue to push the boundaries in the world of autonomous store technology, we wanted to reflect on the evolution of retail technology, learning from the past to prepare for the future of retail.

Last year we released a whitepaper about the history and evolution of the grocery store from the turn of the 20th century until the present day. Below, we share with you the major turning points in the journey toward autonomous retail in an abridged version of our whitepaper. As you’ll travel through the decades, it becomes clear that the grocery retailers who acted fast and stayed ahead of the technological curve were the ones that passed the test of time.

You can download and read the full whitepaper here: 100 Years of Retail: Evolution of Grocery Stores

The origins of the grocery store

During the last century, technological innovations and societal changes were among the main forces changing how people obtained, prepared, and consumed food, and caused grocery stores to constantly evolve.

Until the early 20th century, most American food stores carried only basic products, like sugar, tea, and flour. In this era, most households grew and made all their food at home. Things began to change in the 1910s when more people moved to cities and began shopping for fruit, vegetables, and meat, causing more food stores to open. Developments like refrigeration, cardboard boxes, a national railroad network, and the assembly-line, made it feasible for the first time to produce and distribute fresh food on a larger scale. These advances also led to lower consumer prices and a larger variety of foods.

By the 1920s, it became more common to see more kinds of products in the same place, especially when the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, began opening “economy stores” with all types of food, eventually becoming the well-known A&P brand of grocery stores. Around this time, stores also began letting customers pick out some of their own goods, rather than relying on ordering everything from a clerk behind a counter or stall; this was a key change that enabled stores to cut costs and increase sales volumes. It also led to uniform prices for all shoppers and would continue to drive the development of grocery stores and their focus on a convenient experience for the customer.

Already at this point, consolidation was a strong theme in the industry because profit margins were so thin, and all consumers, even wealthy ones, were conscious of food prices. By 1933, 25% of all grocery sales went to three big chains and each chain ran large networks of warehouses to get better deals on wholesale purchases, effectively taking control of much of the supply chain and lowering prices.

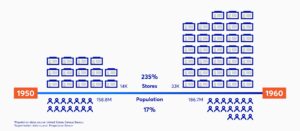

After World War II, new technology, like affordable cars, household appliances, television, and agricultural advances, along with a growing population in the expanding suburbs, further contributed to the increased rise of the supermarket. The number of stores more than doubled from 14,000 in 1950 to 33,000 in 1960. More types of products made their way to store shelves, due to lifestyle changes. Additionally, modern household appliances like toasters, mixers, and refrigerators, which had become common, also inspired new grocery products, like frozen dinners and cake mixes.

Major developments in retail technology shook up the grocery industry

With the advent of computers, the grocery industry was one of the first to embrace them, installing such systems in warehouses as early as the 1960s, and opening the door for this new technology to spread across the entire retail sector.

By the 1970s, computer technology emerged as an important factor in determining store productivity and gaps began to open up between stores with differing levels of technology. The main innovation was the development of barcodes, which first appeared in grocery checkouts in 1974. These scanners and barcodes formed the basis for much of the further technological innovation, including inventory management software, loyalty programs, and coupons. The increasing use of credit and debit cards, which also required stores to invest in equipment and pay processing fees, further sped up the checkout process.

Fast forward to today, when the rise of data analytics and the pandemic shook up the grocery industry like never before. The sharp increase in online shopping, accelerated by COVID, along with growing demand for local products is testing retailers, with many of them ultimately turning to technology to make sure they can adjust to a changing market and still be profitable. About two-thirds of grocery retailers say they plan to increase spending on technology, according to a Progressive Grocer survey. It is now innovation rather than the traditional reliance on getting more customers in the door that is driving growth in groceries, says Laurent Thoumine, retail lead for Europe at Accenture.

Accelerating toward automated retail

In the present day, grocery retailers are embracing technology and innovation to automate different elements of their business to boost efficiency and improve the customer experience. One example of this is in micro-fulfillment systems, which often operate in the back of stores or as separate facilities within easy reach of the customer base. These are the middle road between large warehouses that take up space and often need to be located outside of populated areas, increasing the distances for delivery drivers, and simply picking items for orders off of store shelves. Automation allows these micro centers to be small and compact, and therefore easier to locate near customers, cutting down on delivery time and costs.

Grocers are also increasingly using social media and data analytics, based on customers’ past online orders, to tailor their advertising to individual consumers and stay on point with food trends, like the pandemic-inspired increase in home cooking and baking.

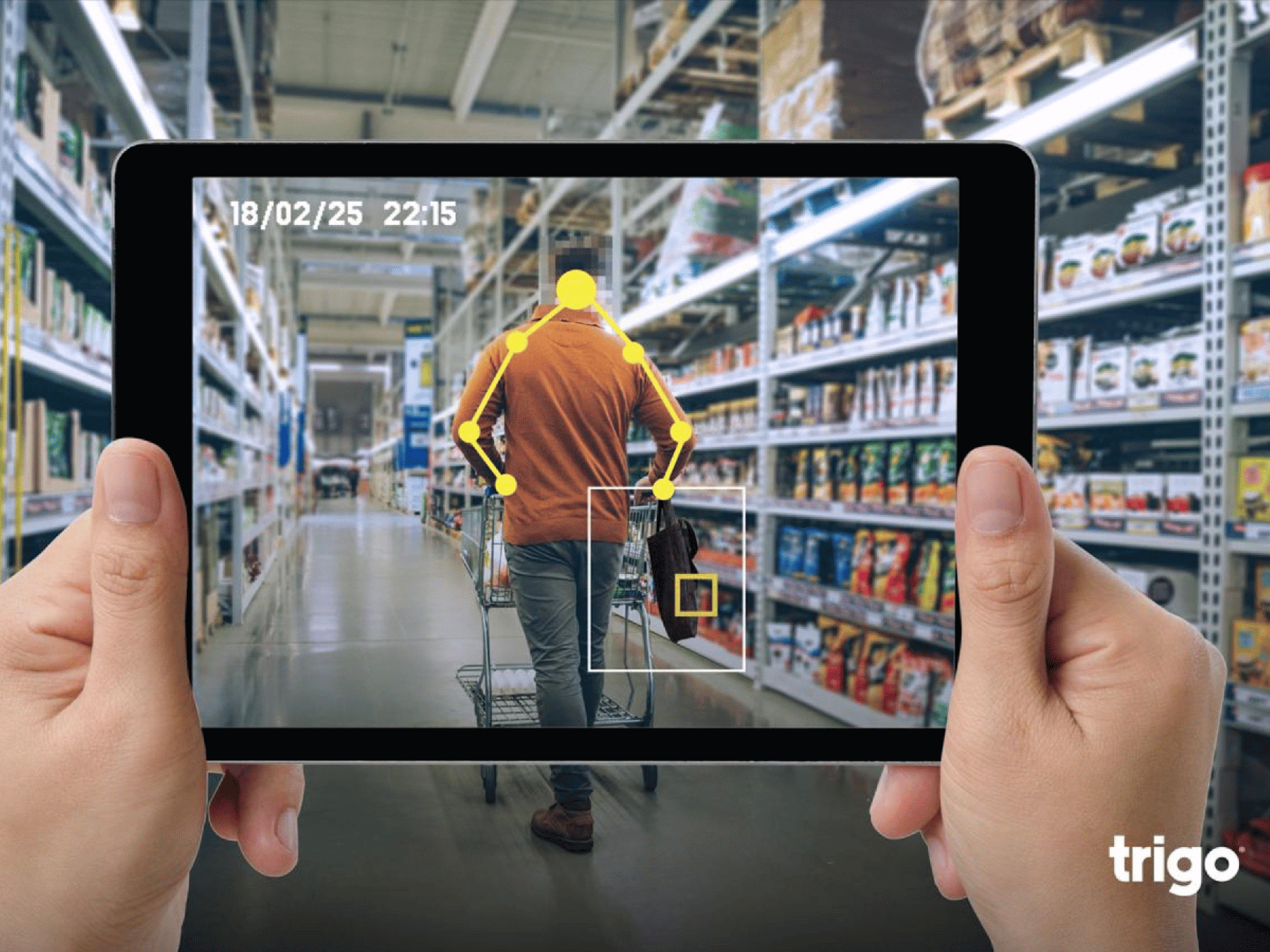

Physical grocery stores are also starting to change, with apps for ordering fresh items from the deli in order to avoid lines, and innovative checkout processes. Israel-based Trigo has outfitted European stores like Tesco with technology that relies on a network of cameras and connected sensors to know which products registered customers put in their baskets, and then automatically charges the credit card on file for them. It retrofits the technology to an existing store, meaning that any store can be transformed into a smart store using Trigo’s solution.

“This will create a better customer experience, which is good for the customers as well as the stores,” Trigo’s CEO Michael Gabay says. “When you have a better customer experience than others, people will come to your store more. And people will buy more; research shows that when they feel good in a store, they buy more. And when people know they don’t need to spend time waiting in line, they are also likely to buy more because they have more time to shop.”

The technology also reduces the need for staff to work at checkout lanes and frees up the space currently used for checking out, allowing stores to use it for merchandise or other purposes that improve the customer experience.

“It just makes the store overall more efficient,” Gabay says.

All of these changes are pushing more grocers to launch technology departments and partner with tech firms to keep up and stay ahead. These partnerships are also driving up stock prices of publicly-traded grocery stores after a decade of falling valuations.

Autonomous stores are the obvious next step in the evolution

Frictionless checkout will likely become more standard across physical stores, says Daniel Williams Hooker, professor of business at Cornell University, who studies the grocery sector. “For the customer, this is a good alternative to online shopping, because you can still pick out what you want – and many people still want to pick out their meat and produce,” he says. “But it’s quick and automated, and saves time.”

The growth of frictionless checkout will likely start in cities and other high-traffic locations, then spread, Gabay explains. He adds that stores will gain additional benefits from this technology in the future, including the ability to know exactly what is on their shelves at any given moment, key to improving supply chains.

Grocery retailers will also increasingly need to pay attention to changing consumer demands and find creative tech-based ways to meet them. For example, consumers will likely want to know more about what they are buying, including how healthy and sustainable it is.

Looking forward, analysts say grocery stores and shopping habits will continue to evolve, with consumer preferences and retailers’ utilization of data driving most of the changes.

Innovations like frictionless checkout and app-based programs for in-person services, like ordering fresh deli meat at the counter, will increasingly allow stores to collect a massive amount of data not only on what customers buy but also on which items they may initially pick and put back, how long they spend in stores, how often they shop and the order in which they navigate aisles. All this data can be crunched and analyzed with artificial intelligence and machine-learning algorithms to help stores make business decisions.

Hooker sees grocery retailers making more money from digital marketing, pointing to the growth of advertising agencies launched by food retailers like Wal-Mart Connect, Kroger Precision Marketing, and Albertsons Performance Media. These departments work with brands to launch advertising on the stores’ channels, not only reaching large audiences of shoppers, but also being able to tailor ads and offers to consumers based on their past purchases or items they have browsed both online and off. Since autonomous store technology is fully digitized and integrated into the in-store shopping experience, it has the potential to provide more granular data to provide these marketing insights and capabilities. The personalization factor that automated retail harness

While services like Instacart will keep those who don’t invest in their own tech in business in the near future, these will likely not be enough in the long run, says Hooker.

“Eventually, retailers who don’t invest in tech won’t last.”